Identifying Candidates for Pellet Hormone Replacement Therapy

By Enrique Jacome MD, FACOG, Bev Blessing, MSN, PHD, FNP-BC

Abstract

In clinical practice, there is a measure of uncertainty regarding selection of appropriate candidates for hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Pellet based hormone therapy presents a unique challenge because it is longer-lasting than more commonly used methods, but it is well liked by many because of its ability to provide a sustained customized approach. Although pellets have been available for 70+ years, they are receiving renewed interest in the media and are included in ongoing discussions in the lay community. As a result, many patients are interested in the potential benefits of pellet HRT and are seeking guidance from their providers. Historically due to concern regarding HRT, a level of caution accompanies the elevated level of interest. Many organizations have agreed that use of HRT is contraindicated for certain patients such as those with previous strokes, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, liver disease and diagnosis of either breast or prostate cancer. However newer studies challenge long held perceptions which makes an individualized assessment more complex. We are proposing a sequenced combination of validated tools to help assess patient candidacy for HRT and to establish an objective baseline score for evaluating progress after treatment. This would include the absolute contraindication list, the Cardiovascular 10-year risk scale, and the Menopause Rating scale for women or the Androgen Deficiency of the Aging Male scale for men. This organized approach should aid in the clinician/patient decision-making process.

Introduction

The current popularity of pellet hormone replacement therapy (HRT) among the general population, including both men and women has placed a demand on clinicians to be prepared to provide knowledge-based guidance, and treatment strategies that are not only effective but safe. With pellet HRT, there are multiple considerations, but the primary starting point would be the patient’s personal risk/benefit profile associated with hormone replacement therapy (HRT). This would include consideration for current medications, medical history, social history, and potential allergies. The second major area of concern are those risks associated with the procedure itself, including the potential for bleeding, infections, extrusion, local reactions, dosing challenges, pain control, insertion technique, and provider experience. This second category, although important is not considered for the purposes of this paper.

The identified risks associated with hormone replacement therapy have gone through many iterations and have been based on lessons learned in various controlled trials and meta-analyses. It is now known that with proper patient selection, our patients can safely take advantage of the many benefits of hormone therapy. This premise is very different from a time when the reports of increased cardiovascular death and cancer were enough reason not to pursue hormone replacement therapy.

Risks of Hormone Replacement Therapy

For women, the most common HRT involves supplementation of declining hormones at or near the time of menopause. This type of therapy is often recommended to relieve common symptoms of menopause and to take advantage of some of the benefits noted with hormone supplementation, such as delaying/minimizing bone loss. The most common combinations include estrogen alone or estrogen with a progestogen such as progesterone, or a synthetic progestin. Other variations may include the use of testosterone, DHEA, pregnenolone, and or melatonin.

The availability of hormone replacement products and the growing demand from the public to benefit from them warrants a careful look by the clinician. The most recognized body of study about the risks and benefits of HRT in women comes from the randomized control trials, sponsored by the National Institute of Health as part of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) (Stefanick, M, et al.). These included the:

- The WHI Estrogen-plus-Progestin Study, in which women with a uterus were randomly assigned to receive either a hormone medication containing both estrogen and progestin (Prempro™) or a placebo.

- The WHI Estrogen-Alone Study, in which women without a uterus were randomly assigned to receive either a hormone medication containing estrogen alone (Premarin™) or a placebo.

More than 27,000 healthy women who were 50 to79 years of age at the time of enrollment took part in the two trials. The primary focus of the study was to explore potential beneficial effects of hormones on disease prevention like cardiovascular disease, breast cancer, and fracture prevention. Although both trials were stopped prematurely (in 2002 and 2004, respectively) when it was believed that both types of therapy were associated with specific health risks, longer-term follow up of the participants continues to provide new information about the health effects of hormone therapy (The Women’s Health Initiative Study Group).

For example, in a recent analysis on the findings of the WHI studies, the researchers found there was no difference in cardiovascular risk in the younger women in the study and the placebo group. But the older women >60, who initiated hormone therapy later with the oral meds had an increased risk due to the impact on atheromatous plaque that had built up in those years prior to using hormone therapy (Manson, J, et al.). Conversely, a study on transdermal estradiol showed that by avoiding first pass metabolism in the liver, the overproduction of triglycerides was inhibited, which resulted in a lower systolic blood pressure, and increased stroke volume. As a result, this transdermal method of delivery decreased the risk of cardiovascular events (Mohammed, K, et al.). It is interesting to note that the long-term CVD death rate was higher in the WHI placebo group than in the test groups. There was also an increased risk of breast cancer with the estrogen/progestin arm in the study, but there was a reduction in breast cancer in the estrogen alone group. The all-cause mortality was higher in the placebo group than for either arms of the study, but especially in the younger group with a 33% difference (Manson, J, et al.). Finally, the total cancer death rate was neutral across both studies.

For the male, the primary focus for hormone replacement has been on testosterone. Again, the knowledge base for this is constantly changing. It is well known that testosterone impacts the brain, peripheral nerves, muscles, fat, bone, cardiovascular system and the reproductive system. Low levels may increase the risk for diabetes and metabolic syndrome, contribute to bone mineral density (BMD) loss, and is associated with both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality (Morgentaler, A, et al.). In an international consensus position on testosterone deficiency reviewing available knowledge base and research, the group agreed there was no increased risk for cardiovascular events in men or increased risk of prostate cancer with testosterone therapy. It was found that testosterone increases lean muscle mass, and it may improve glycemic control. There are no specific recommendations regarding age, but the potential for erythrocytosis should be monitored and addressed when indicated. Additionally, mortality rates were reduced by half in men with known deficiency when treated, compared to untreated men. Even with the known benefits, potential worsening of prostate cancer, prostate hyperplasia, polycythemias, and obstructive sleep apnea should be considered when evaluating candidacy (Osterberg, E, et al.)

Assessing Risk at the Individual Level

It is evident new data and perspectives are forever emerging in medicine. Therefore, an organized strategy may prove beneficial in discussing this information with our patients considering pellet hormone replacement therapy. A three-step approach therefore is being recommended.

- Evaluate for absolute and relative contraindications to hormone therapy

- Assess risk for long term cardiovascular disease

- Clearly understand the symptoms and concerns of the patient

The first step is to understand the absolute and relative risks of hormone therapy. Although absolute contraindications don’t seem to really exist, most areas of concern are relative risks. These could include:

- history of cancer (endometrial, breast, prostate)

- severe active liver disease

- thromboembolic disorders

- heart disease

- unexplained bleeding

- anaphylaxis of unknown causes (Kaur)

Patients with self assessed sensitivities, drug abuse/polypharmacy disorders and psychiatric conditions should also be assessed carefully. Other considerations would be:

- patient with a pacemaker or valve disease

- atrial fibrillation on anticoagulants

- coronary artery disease

- hypertriglyceridemia

- autoimmune disease

- HIV

- elevated PSA

- patients with multiple breast biopsies

- endometriosis

- fibroids

- smokers

Although patients with these issues may be candidates for hormone replacement, additional consideration may be necessary such as addressing the impact of anticoagulants on pellet implantation, need for SBE prophylaxis, or an endometrial biopsy to evaluate bleeding issues. Taking time to discuss these additional considerations will be important in developing the plan for care.

The second step is to generally evaluate the patient for cardiovascular risk. The ACC/AHA developed a simple calculator that uses common information to screen for CVD risk (Goff, D, et al.). The experienced clinician starts by evaluating the patient for general risk factors to include hypertension, diabetes, smoking, family history, chronic kidney disease, and obesity. Then simply using the CVD risk calculator the HDL and total cholesterol can be used in combination with age, BP, race, hypertensive medications, and history of diabetes to determine a risk factor. Less than 5% is low risk, 5-7.5% is intermediate risk, and > 7.5% is high risk (Wilson). The higher risk patient may still be a candidate for HRT, but it may indicate a need to decrease the dosage, refer for further assessment with a cardiologist or internist, or follow different labs to assess any early indicators for change. The calculator can be located at http://www.cvriskcalculator.com/. It has been criticized by some for overestimating risk but can be helpful in honing-in on patients that need further consideration.

Finally, the third assessment is related to the symptoms that need to be addressed. Two commonly used tools have been validated to assess symptoms related to hormone changes. The Menopausal-Rating Scale (MRS) for women and the Androgen Deficiency in Aging Males (ADAM) for men.

The MRS has 11 questions, with ratings from 0-4, covering psychiatric related changes, somatic complaints, and urogenital symptomology. Having the patient complete the questionnaire prior to treatment, provides an objective baseline starting point, as well as an indication of where to best address therapy. The higher the score the worse the symptomology but the greater potential for improvement. Population studies have determined that patients with little/no complaints before therapy improved by 11% with HRT, those with mild complaints at entry by 32%, with moderate by 44%, and with severe symptoms by 55% compared with the baseline score (Heinemann, L, et al.). The 11 items include the following:

- Hot flushes, sweating (episodes of sweating)

- Heart discomfort (unusual awareness of heart beat, heart skipping, heart racing, tightness)

- Sleep problems (difficulty in falling asleep, difficulty in sleeping through, waking up early)

- Depressive mood (feeling down, sad, on the verge of tears, lack of drive, mood swings)

- Irritability (feeling nervous, inner tension, feeling aggressive)

- Anxiety (inner restlessness, feeling panicky)

- Physical and mental exhaustion (general decrease in performance, impaired memory, decrease in concentration, forgetfulness)

- Sexual problems (change in sexual desire, in sexual activity and satisfaction)

- Bladder problems (difficulty in urinating, increased need to urinate, bladder incontinence)

- Dryness of vagina (sensation of dryness or burning in the vagina, difficulty with sexual intercourse)

- Joint and muscular discomfort (pain in the joints, rheumatoid complaints)

The total score of the MRS ranges between 0 (asymptomatic) and 44 (highest degree of complaints). The minimal/maximal scores vary between the three dimensions depending on the number of complaints allocated to the respective dimension of symptoms:

- Psychological symptoms: 0 to 16 scoring points ( 4 symptoms: depressed, irritable, anxious, exhausted)

- Somato-vegetative symptoms: 0 to 16 points (4 symptoms: sweating/flush, cardiac complaints, sleeping disorders, joint & muscle complaints)

- Urogenital symptoms: 0 to 12 points (3 symptoms: sexual problems, urinary complaints, vaginal dryness).

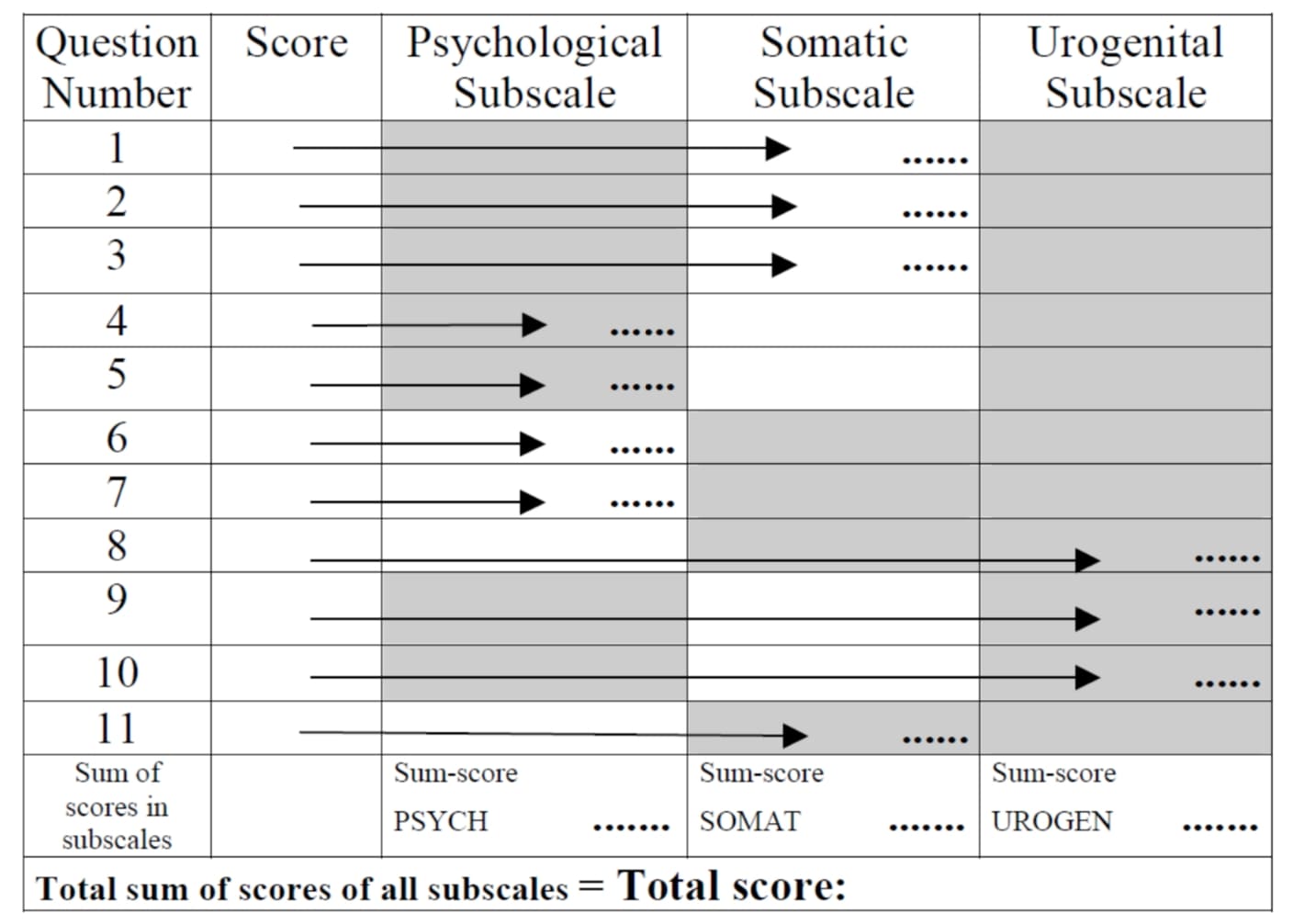

The composite scores for each of the dimensions (sub-scales) is based on adding up the scores of the items of the respective dimensions. The composite score (total score) is the sum of the dimension scores (Heinemann, L, et al.).

The scoring scheme of the MRS scale is simple:

- The questionnaire has for each of the 11 item an option to check one of 5 degrees of severity of symptoms (severity 0 [none]...5 [very severe] points at the questionnaire),

- The scoring points of each of the items can be placed into the form below

- The composite scores for each of the three dimensions (sub-scales) is based on adding up the scores of the items of the respective dimensions.

- The composite score (total score) is the sum of the three dimension scores.

The “total score” is the sum of the scores of the three subscales.

The conclusion of the creators of the MRS is that a score improvement of at least 4 to 7 points is recommended to establish clinically meaningful efficacy.

So, as an example of how this could be used, if a woman’s MRS score was low and she had any potential risk factors for cardiovascular disease or cancer, the benefit to risk ratio would be small and the clinician would be prudent to advise against pellet HRT. However, if a woman’s MRS score was in the higher range of possible scores and she had no risk factors, she most likely represents a good candidate for pellet HRT.

The ADAM scale has been used to assess androgen deficiency. It has 10 “yes or no” questions and an 88% sensitivity and 60% specificity (Mohamed, O, et al.). Because it is “yes or no” answers rather than a Likert type of scale, there is very little opportunity to grade for varying degrees of change. Although criticized for its lower specificity scores, when combined with testosterone levels, it can provide an excellent starting place for assessment and establish a baseline for following improvement in symptomology.

The questions include the following:

- Do you have a decrease in libido (sexdrive)?

- Do you have a lack of energy?

- Do you have a decrease in strength and/or endurance?

- Have you lost height?

- Have you noticed a decreased "enjoyment of life"?

- Are you sad and/or grumpy?

- Are your erections less strong?

- Have you noted a recent deterioration in your ability to play sports?

- Are you falling asleep after dinner?

- Has there been a recent deterioration in your work performance?

The rationale for the questions is based on previous studies that demonstrated that as testosterone levels decline, certain symptoms are more commonly present in males based on the low bioavailable testosterone levels. The questionnaire is given as part of the initial evaluation and used to determine whether blood testosterone levels should be drawn with the objective of identifying men who should receive pellet HRT with testosterone (Morley, J, et al.)

A positive result on the ADAM questionnaire is defined as an affirmative answer (‘‘yes’’) to questions 1 or 7 or any 3 other questions.

So, as an example of how this could be used clinically, if a man does not have a positive result on the ADAM questionnaire, it may not even be necessary to draw blood testosterone levels. Those with a positive result are more likely to have low bioavailable testosterone levels and be considered for pellet HRT, if the cardiovascular risk profile is suitable, and the patient has no risks associated with prostate cancer.

Conclusion

More and more patients are interested in getting the longer-lasting hormone pellet for treatment of hormone related symptomology. The three-step approach of assessing relative / absolute contraindications and cardiovascular risk, then establishing an objective baseline for evaluating treatment seems to be an effective organized approach to assessment and counselling for these patients. The proposed tools are readily available and at no cost to the user. The results can then be incorporated into the patient’s medical record to document the assessment and counselling process.

Dr. Jacome is a pioneer and innovator with a unique background in minimally invasive surgery and hormone pellet insertion. Bev Blessing and Dr. Jacome are committed to improving the insertion technique. Email info@pellecome.com or 888.773.9969.

References

Goff, D, et al. “ACC/AHA Guideline on Assessment of cardiovascular risk: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines.” Circulation, vol. 129, 12 Nov 2013, pp. S49-S73, doi:10.1161/01.cir.00043771.41’4860.6.98.

Heinemann, L, et al. “The Menopause Rating Scale (MRS) as outcome measure for hormone treatment? A validation study.” Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, vol. 2, no. 67, 22 November 2014, pp. 1-7, doi:10.1186/1477-7525-2-67.

Kaur, K. “Menopausal hormone replacement therapy.” Medscape, 4 Jan 2018.

Manson, J, et al. “Menopausal hormone therapy and long term all cause and cause specific mortality: The Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials.” JAMA, vol. 318, no. 10, 2017, pp. 927-938, doi:10.1001/jama.2017.11217.

Mohamed, O, et al. “The quantitative ADAM questionnaire: a new tool in quantifying the severity of hypogonadism.” International Journal of Impotence Research, vol. 22, no. 1, 2010, pp. 20-24, doi:10.1038/ijir.2009.35.

Mohammed, K, et al. “Oral vs transdermal estrogen therapy and vascular events: A systematic review and meta-Analysis.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 100, no. 11, 2015, pp. 4012-4020, doi:10.1210/jc.2015-2237.

Morgentaler, A, et al. “Fundamental concepts regarding testosterone deficiency and treatment: International Expert Consensus resolutions.” Mayo Clinical Proceedings, vol. 91, no. 7, 2016, pp. 881-896, doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.04.007.

Morley, J, et al. “Validation of a screening questionnaire for androgen deficiency in aging males.” Metabolism, vol. 49, no. 9, Sep 2000, pp. 1239-1242, doi:10.1053/meta.2000.8625.

Osterberg, E, et al. “Risks of testosterone replacement therapy in men.” Indian Journal of Urology, vol. 30, no. 1, 2014, pp. 2-7, doi:10.4103/0970-1591.124197.

Stefanick, M, et al. “The Women’s Health Initiative postmenopausal hormone trials: Overview and baseline characteristics of participants.” Annals of Epidemiology, vol. 13, 2003, pp. S78-S86, doi:10.1016/S1047-2797(03)00045-0.

The Women’s Health Initiative Study Group. “Design of the Women’s Health Initiative clinical trial and observational study.” Controlled Clinical Trials, vol. 19, 1998, pp. 61-109.

Wilson, P. “Cardiovascular disease risk assessment for primary prevention: Our approach.” UpToDate, July 2018.